Peirce Mill is a typical 19th century gristmill

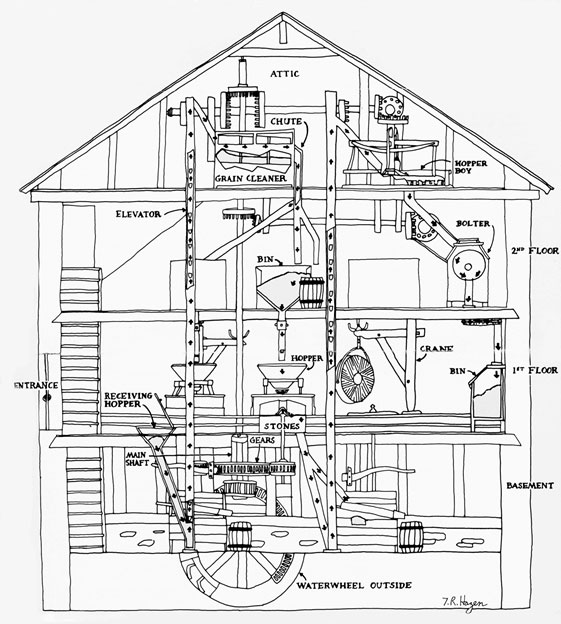

The mill and its machinery are powered by the force of gravity as water pours over the water wheel and causes it to turn. The main shaft of the water wheel enters the mill in the basement, where a complex assortment of oaken gears and shafts mesh together to power machinery located on all four floors of the mill. Originally, about 60 to 70 percent of the power was used to turn the millstones that grind grain into flour; the rest of the energy went to the other grain- and flour-processing equipment positioned throughout the mill. Not all of that equipment has yet been restored to operating condition. The long-term goal of the Friends of Peirce Mill is to see that the entire system can once again operate as it did when the mill’s first restoration occurred in the 1930s. The major aspects of the mill’s mechanical function are outlined below.

Originally, water from Rock Creek was diverted by a partial dam upstream into a narrow channel (called a millrace) that brought it over the water wheel and then drained it back out to the creek. The path of the old millrace (long gone) from the creek to the water wheel is now marked by two lines of stones. As water flowed from the millrace on to the water wheel, troughs built into the water wheel filled, and the weight of the filled troughs brought them down and caused the wheel to turn. Because it is impractical for environmental reasons to use creek water today, the water that feeds the wheel comes from the municipal water supply and circulates in a “closed-loop” system. Though the water is pumped into the mill race by modern equipment, the force of gravity as the water flows on to the wheel still drives the wheel and the mill’s machinery, just as it always has.

Originally, grain was brought into the mill on the first floor and dumped into the receiving hopper that stands just inside the front entrance. Flowing down to the basement through a wooden chute, the grain was then lifted by an elevator to the top (attic) floor of the mill. The mill’s elevators are narrow enclosed chutes that carried the grain in metal cups affixed to leather belts. In the attic, the grain then passed through a double-mesh grain cleaner, essentially a large sifter designed to remove sticks, pebbles, and other foreign matter, thus ensuring that only pure grain would continue on for grinding. That grain then descended through more chutes to storage bins on the second floor, where it waited to drop into hoppers positioned just above the millstones on the first floor. While the machinery for this process is in place, it is not currently operational. Until it is restored, the current miller bypasses the grain cleaning process by pouring already-clean grain directly into the hopper over the millstones.

There are three pairs of millstones at Pierce Mill, one of which is currently in operation. The massive stones weigh 2,400 pounds each. One pair, made of quartz and imported from France, was intended for grinding wheat into fine flour; it was purchased for the mill in 1880 for 75 dollars. The stones for grinding corn are made of local granite. Each pair of stones consists of a fixed bed stone, which is mounted on the mill floor and doesn’t move, and a running stone, which spins at 125 revolutions per minute a fraction of an inch above the bed stone, never touching it. Grain is fed in at the center of the running stone, and the turning of the stone shears the grain without crushing it. Centrifugal force carries the cut grain, called meal, through chiseled grooves in the bed stone to the rim of the millstones, where it collected in a vat and funneled down to the basement.

The hopper filled with corn sits just above the millstones.

Today the ground meal (corn meal) is sifted and ends its journey in a bin in the basement. However, originally the warm, moist, freshly-ground meal would have ridden another grain elevator back up to the mill’s attic, where it would have fallen on to a round, spinning device known as a hopper boy. The hopper boy has a rake that spreads the meal evenly over its surface, allowing it to cool and dry, a function originally performed manually by boys with rakes. Once the meal was cool and dry, it would descend to the mill’s second floor, where a large barrel-shaped sifting device called a bolter separated flour from bran and “middlings” (bran flakes and coarser flour). These finished products then fell through more chutes into holding bins on the first floor, where traditionally they were packed into barrels for shipment to market. Peirce Mill could process upwards of 50 barrels of flour a day during times of peak demand. Peirce Mill’s hopper boy and bolter are in place for visitors to inspect, but they are not currently operational. Hopefully they will be restored at a future date.

In addition to the elevator system for transporting grain up and down inside the mill, the mill also has a barrel hoist capable of lifting heavy barrels of grain from one floor to another. Through the initiative of the Friends of Peirce Mill, the barrel hoist was restored in 2016 and is now once again functioning as it did in the past. The barrel hoist is not an integral part of the mill’s operating machinery, but it was an invaluable tool to assist the miller in the day-to-day activities of the mill.

Oliver Evans (Source: Library of Congress)

The mill’s automated mechanisms—the system of elevators, hopper boy, bolter, and other equipment—represented a revolution in efficiency and productivity that occurred just at the time Peirce Mill was built and was likely incorporated into the mill’s design. In 1795, an inventor from Delaware, Oliver Evans (1755-1819), perfected this system and received one of the first American patents for it. The system produced superior flour with dramatically less labor. A miller and one or two helpers could run Peirce Mill, whereas an older mill without automation might require seven people to perform the same functions.