The Republic Built on Flour

by Yong Kwon

Grinding wheat into flour, grist mills played a significant role in not only feeding the United States after its independence, but also keeping its economy upright. Even after the war was formally concluded in 1783, Britain wanted to punish the United States by preventing goods produced in the new Republic from being sold in the empire’s remaining colonies. But flour was one product that was in such high demand that no colonial official could prevent American merchants from selling it, notably in Britain’s lucrative sugar-cultivating colonies of the Caribbean. The revenue from this flour trade helped sustain and rebuild a country that was heavily indebted and damaged from a costly war during its crucial formative years.

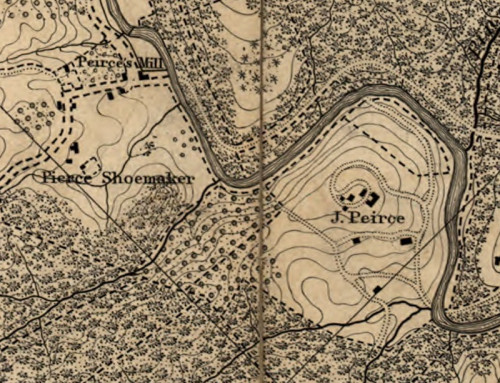

Although these events occurred decades before the construction of Peirce Mill in 1829, they help explain how and why the mid-Atlantic states of the United States in particular emerged as an important producer of flour. Simultaneously, the ties between American flour and Caribbean sugar cultivation bring to light another way the new Republic was partly complicit in human trafficking that occurred across the Atlantic Ocean.

High-quality flour is so readily available today that we forget that it was once one of the most sought-after products in the 18th and 19th centuries. For Europe’s empires, the availability of milled grain was closely linked to the maintenance of profitable colonial ventures. The ability to supply plantations in far-flung island possessions with food meant that all the land and (forced) labor there could be dedicated to growing a cash crop – this was particularly important for colonies in the Caribbean where the cultivation of sugar cane was incredibly profitable. [1]

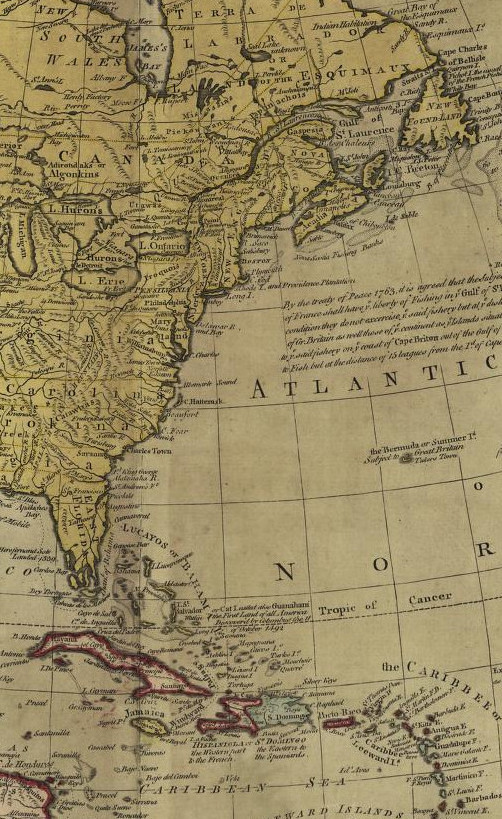

The value of sugar to European empires is difficult to convey to modern audiences. At the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, the victorious British gave the defeated French government the choice of surrendering either its vast possessions in Canada and the Mississippi River Basin or its tiny Caribbean island colonies like Guadeloupe and Martinique where slaves grew and processed sugar canes. Paris chose to hold on to sugar.

Given the importance of sugar production, the imperative to deliver flour to sugar-growing colonies like Jamaica or Antigua was high. However, the wet climate of the British Isles meant that flour milled there carried a high moisture content and would spoil during ocean voyages across the Atlantic Ocean. [2] The search for a drier climate to mill flour brought Britain’s imperial spotlight on its North American possessions. Most notably, places like the Eastern Shore of Maryland had soil that was not very conducive to the cultivation of tobacco – the cash crop of surrounding colonies – but very suited to wheat. The locally grown grain was then milled, packaged, and shipped to sugar colonies from nearby port cities like Baltimore and Philadelphia, fostering commerce and new wealth in the mid-Atlantic region.

By the time the dispute over local autonomy in the 13 colonies led to the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775, both wheat cultivation and flour milling were key features of the North American economy.

At the war’s end, the American economy was severely battered. Countless farms and workshops were destroyed in the fighting, and the British army occupied key ports like Boston, New York, Charleston, and Philadelphia during various points of the conflict. Some economic historians estimate that the decline in the average income during the War for Independence was nearly as severe as that during the Great Depression of the early 1930s. [3]

Compounding the challenge of rebuilding, the British government banned American shipping and several American goods from entering its colonies in the Caribbean. [4] As a consequence, American exports to Britain and its colonies only returned to half of their pre-war levels (about £2.5 million) while the import of British goods soared (£7.6 million) between 1784 and 1786. [4] This trade imbalance during this period required the United States to sell its gold and silver, reducing the availability of these precious metals for both the repayment of war debts and investment in the domestic economic recovery.

One of the few bright spots during these hard times was the export of American flour, especially flour from the mid-Atlantic states shipped out from Baltimore. Britain’s plan to substitute American flour with Canadian products fell short as the latter could not produce sufficient amounts to satisfy demand in the Caribbean. Marylanders in particular took advantage of the continued demand for foodstuffs in Britain’s sugar colonies as the State’s wheat farms came away from the war relatively unscathed compared to peers in the Delaware Valley, where some of the most ferocious fighting between the British and Continental armies took place. Moreover, Baltimore had escaped the war without being occupied or blockaded – unlike Philadelphia or New York – which meant that overseas commerce could continue uninterrupted from its port. [5]

Successive crop failures in France (1784, 88, and 89) opened new opportunities for American flour exports outside the British Empire. The deepening conflict between Britain and Napoleonic France in the early 19th century created further opportunities for farmers, millers, and grain dealers across the young nation as European soldiers and civilians alike needed to be fed while the fighting interrupted agricultural production from Spain to Russia.

Flour exports to the Caribbean between 1790 and 1792 grew to 400,000 barrels, far exceeding 233,000 barrels sold during the pre-war years between 1768 and 1772. Similarly, flour exports to northern Europe also grew from 35,000 barrels (1768-72) to 102,000 barrels (1790-92). [6]

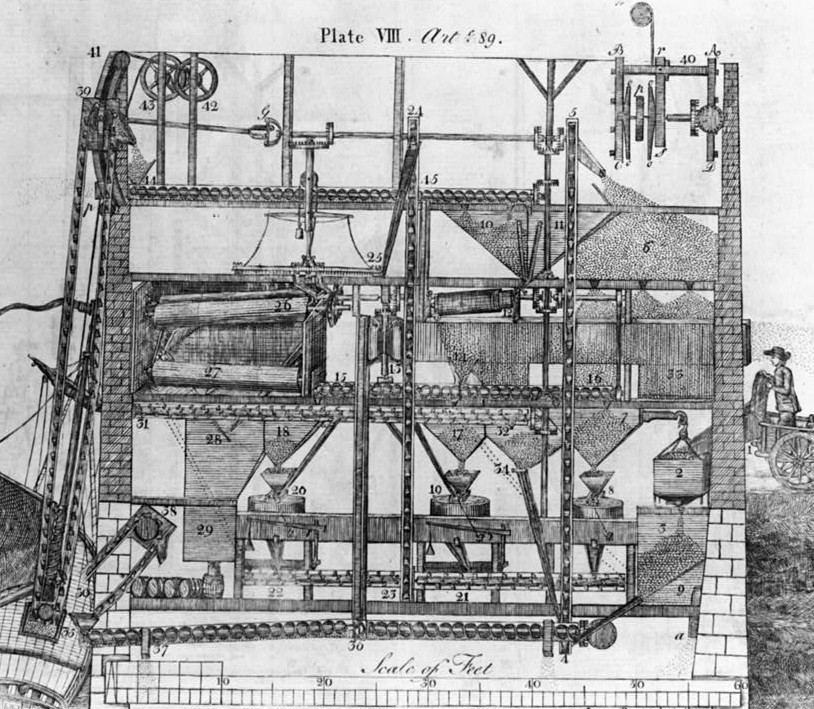

In the late 18th century, Oliver Evans invented an automated system that revolutionized milling in the Mid-Atlantic.

Building on this commercial success, the United States increasingly found its political and economic footing. At a time when the young Republic was most vulnerable, flour proved to be an all-important commodity that kept the proverbial lights on. Grist mills tell part of that story.

However, it is also important to reflect on what America’s role in keeping the Caribbean plantations supplied with food meant for the continuation of slave-based cultivation of sugar there. Between 1776 and 1800 alone, over 800,000 people were kidnapped from Africa and trafficked to the Americas. A vast majority of these people were forcibly held in the Caribbean to work on these sugar plantations under brutal conditions. [7] While much of the discussions around slavery in American history rightly emphasizes the forced labor that took place within our country, the importance of American flour for the operation of sugar colonies in the Caribbean underscores a less well-told story of this country’s complicity in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

This is not a straightforward story of triumph, but one that offers reflections on how seemingly positive developments for some also have unintended negative consequences for many others.

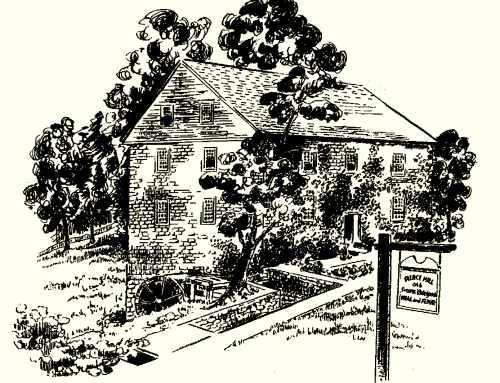

Though Peirce Mill was built 50 years after the Declaration of Independence, and did not grind flour for the export market, Washington’s last working gristmill continues to tell the story of milling in the Mid-Atlantic.

Footnotes

[1] Sidney Mintz. “Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History.” Penguin Books. (1986).

[2] G. Terry Sharrer. “The Merchant-Millers: Baltimore’s Flour Milling Industry, 1783-1860.” Agricultural History, Vol. 56, No. 1, Symposium on the History of Agricultural Trade and Marketing (Jan., 1982), pp. 138-150. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3742305

[3] Peter H. Lindert, Jeffrey G. Williamson. “American Incomes before and after the Revolution.” NBER Working Paper 17211 (February 2013). https://www.nber.org/papers/w17211

[4] Douglas A. Irwin. “Clashing over Commerce: A History of U.S. Trade Policy.” University of Chicago Press (2017). https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c13851/c13851.pdf

[5] Geoffrey N. Gilbert “Baltimore’s Flour Trade to the Caribbean, 1750-1815.” The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 37, No. 1, The Tasks of Economic History (Mar., 1977), pp. 249-251. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2119461

[6] Brooke Hunter. “The Prospect of Independent Americans: The Grain Trade and Economic Development during the 1780s.” Explorations in Early American Culture, Vol. 5 (2001), pp. 260-287. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23549287

[7] Explore the origins and forced relocations of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic World. Slave Voyages. (n.d.). https://www.slavevoyages.org/