Women in Preservation:

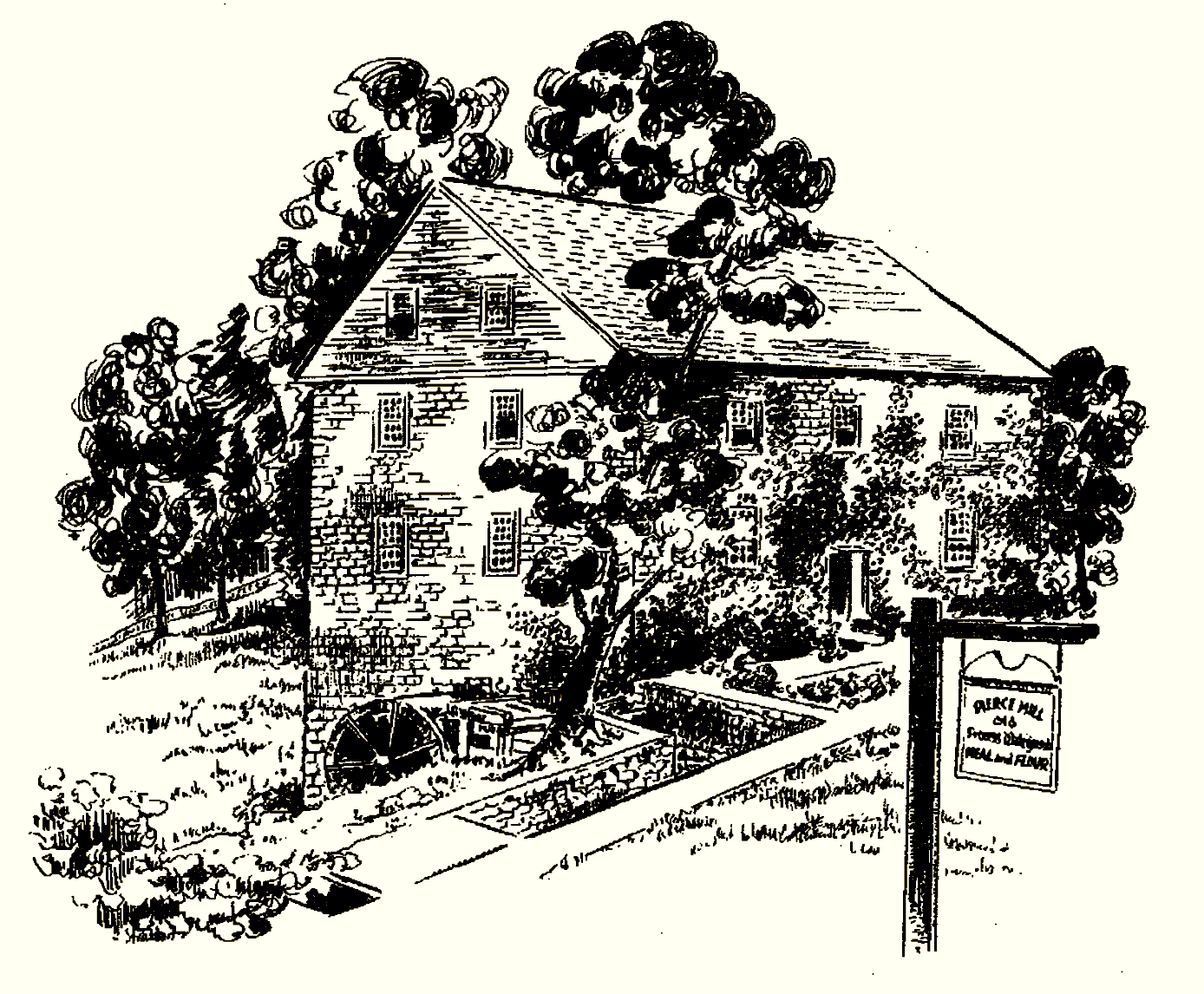

Ruth Butler & the Historic American Buildings Survey of Peirce Mill

In the mid-1930s, the federal government sent a team of architects, historians, and photographers to Rock Creek Park to produce a detailed report on Peirce Mill–part of a New Deal effort known as the Historic American Buildings Survey.

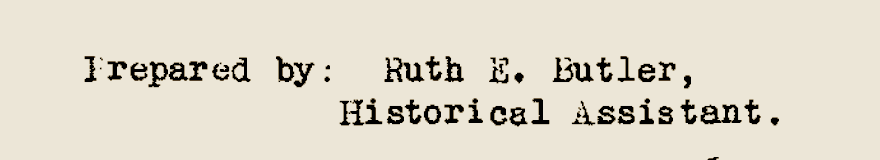

The Historic American Buildings Survey preserved details of Peirce Mill’s history that might otherwise have been lost. This invaluable document was prepared by a woman named Ruth E. Butler. Her official title was “Historical Assistant,” but she was clearly more than a typist. Butler belonged to a generation of women challenging traditional gender roles and shaping the new field of historic preservation.

Women worked for the Historic American Buildings Survey as secretaries, stenographers, and assistants–titles that didn’t always match the jobs they performed.

When Ruth Butler arrived at Peirce Mill, the building had been used as a teahouse for three decades. Park managers had expanded the restaurant a few years earlier, adding a screened porch that covered any evidence of the old waterwheel and millrace. By the 1930s, Washington had become a modern metropolis, and the mill was a just picturesque relic of the city’s past. Fewer Washingtonians remembered a time when farmers brought grain to the mill.

The screened porch was added around 1930–and torn down a few years later when the mill was restored.

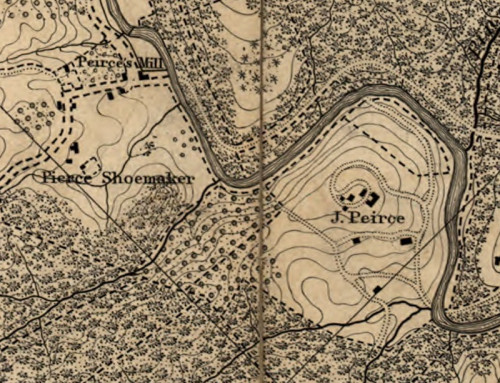

But at the least one city resident remembered the mill in its heyday. Francis Shoemaker was a descendant of Isaac Peirce, who built the mill, and a son of the building’s last private owner. The family’s estate became part of the new Rock Creek Park in 1892, but Shoemaker continued working at the gristmill until 1897, when the old machinery finally failed.

Francis Shoemaker returned to Peirce Mill in November 1934, when he was interviewed for the Historic American Buildings Survey. Ruth Butler was there that day, and recorded Shoemaker’s recollections in her final report. Now in his 70s, Shoemaker described what the mill looked like when he was a boy.

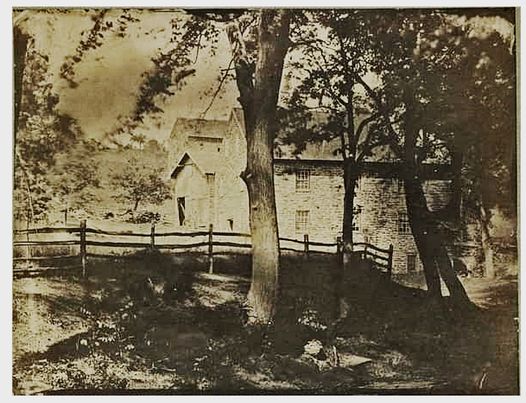

Titian Ramsay Peale photographed Peirce Mill about three years before Francis Shoemaker was born.

Shoemaker recognized the old miller’s desk, still sitting in the teahouse. The millstones were there too, and Shoemaker recalled purchasing one of them in 1880. He pointed out the location of the old mill dam, upstream from the teahouse’s scenic waterfall. Butler recorded these physical details in her report. She also included this vivid scene from Shoemaker’s memories of the 1860s, when business was booming at Peirce Mill:

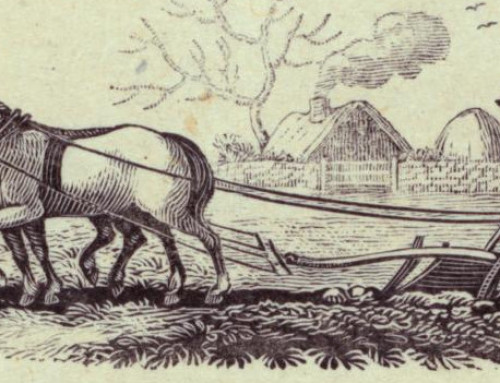

Saturdays presented a scene of great activity in the vicinity of the old mill. The horses and teams were so many around the mill door that it was difficult to get by.

The report Ruth Butler produced was just a few pages long, but it presented the evidence for restoring Peirce Mill. The Historic American Buildings Survey was not just a record of the mill’s past; it was part of a larger New-Deal effort to rebuild the mill’s machinery and resume grinding grain on Rock Creek. The project was never just about jobs for architects and construction workers. In a rapidly changing landscape, the federal government acted to preserve some evidence of the past. In October 1934, C. Marshall Finnan, the superintendent of Rock Creek Park, argued for the preservation of Peirce Mill:

It is the belief of the Park Service that as an educational project from the standpoint of history of early Washington, it is vitally important to preserve this mill.

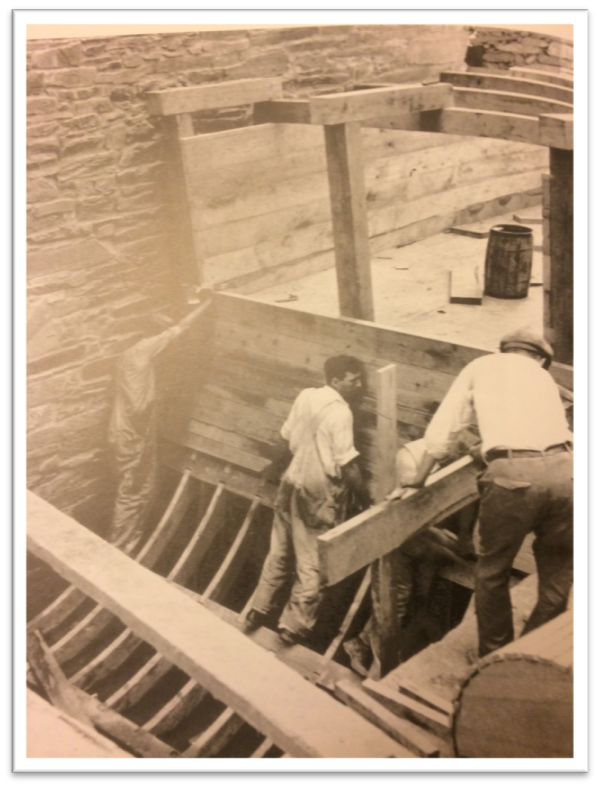

With funding from the Works Progress Administration, the National Park Service restored Peirce Mill in the mid-1930s. They rebuilt the millrace, the waterwheel, and the wooden machinery. The Historic American Building Survey provided some of the information needed to turn the teahouse back into a working gristmill; the rest was educated guesswork.

When Peirce Mill reopened in January 1937, more than two thousand people showed up to see Washington’s last working gristmill in action. An article in the next day’s Washington Post does not mention if Ruth Butler was among them.