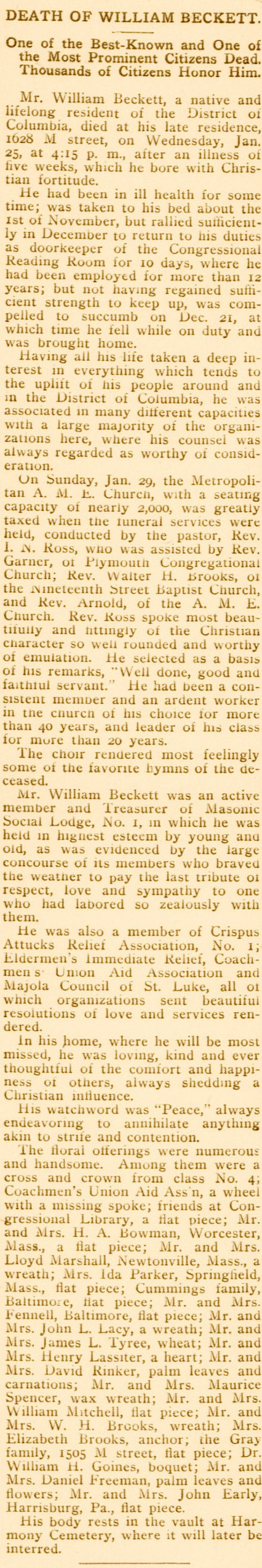

The crowds of mourners at William Beckett’s funeral on January 29, 1911 “greatly taxed” the ample seating capacity of the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church on M Street Northwest. More than two thousand people came on a rainy winter Sunday to remember a man the Washington Bee described as “(h)aving all his life taken a deep interest in everything which tends to the uplift of his people around and in the District of Columbia.” His full obituary, published here, only begins to describe Beckett’s remarkable life.

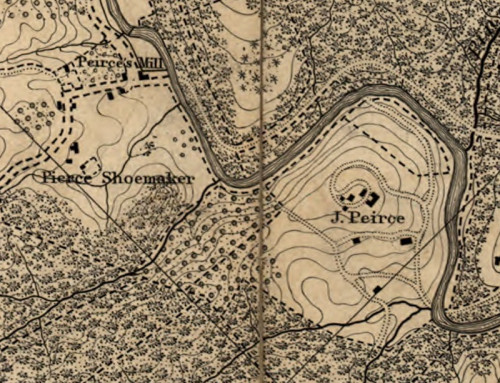

At the time of his death, Beckett was employed as a doorkeeper for the Library of Congress, and he spent his final days at his home on M Street, across from the Charles Sumner School. A lifelong DC resident, Beckett’s birthplace was just three miles from where he died. But he began life under very different circumstances. William Beckett was born some time in the 1830s in rural Washington County, where he was enslaved on Joshua Peirce’s Linnaean Hill estate. Newly discovered evidence suggests that Beckett was also Peirce’s son. His mother was Mary Beckett, who was enslaved by Peirce at the age of fourteen.

Before the Civil War, Joshua Peirce built a successful horticultural business on Linnaean Hill, just south of his father’s gristmill. The nursery sold fruit trees, flowers, and ornamental shrubs, and was known as “Peirce’s pleasure garden.” But Peirce used enslaved workers to run his estate, and relied on William Beckett to manage the nursery. Beckett’s importance became clear after the emancipation of Washington’s enslaved residents in 1862. Peirce–like other District slaveholders–filed a claim to be compensated for the loss of “property.” In his petition, Joshua Peirce described Beckett as the “foreman in my garden greenhouse, and nursery…familiar with various branches of that [gardening] business.” Beckett could also “read and write well” and was a “good coachman.”

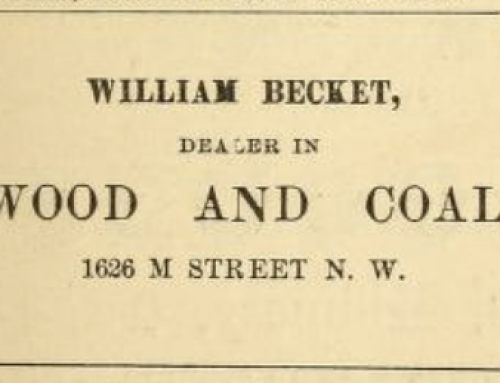

After emancipation, William Beckett returned to manage Joshua Peirce’s plant nursery as a free man. Beckett was so indispensable that Peirce told an associate that it was “impossible to carry on his business without him.” When Peirce died in 1869, he left Beckett a bequest of land and cash valued at $3000, which Beckett appears to have used to purchase a business of his own–a wood and coal yard near the intersection of 17th and M Streets Northwest. Beckett and his wife, Elizabeth, raised a family in the house next door. Beckett eventually sold the business, but lived in the home for the rest of his life.

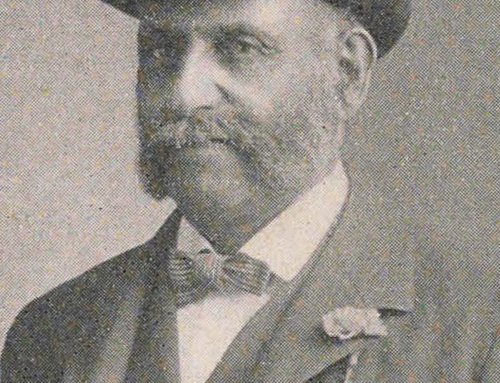

Beckett also worked as a coachman, and in his later years landed a prestigious assignment driving President Grover Cleveland’s carriage. An 1895 newspaper article described Beckett as a “large, handsome man of commanding height and dignified bearing,” with fashionably bushy “Dundreary” whiskers.

Beckett assumed his final post at the Library of Congress in 1900, when he was almost 70 years old. He was a doorkeeper there for ten years, until poor health forced him to leave that post. Despite a debilitating illness, Beckett insisted upon returning to work for ten days near the end of 1910. According to his obituary, Beckett was “compelled to succumb on December 21, at which time he fell ill while on duty and was brought home.”

Along with his obituary, the Washington Bee published a long and detailed list of the people who made floral offerings at William Beckett’s funeral, and wrote that, “In his home, where he will be most missed, he was loving, kind, and ever thoughtful of the comfort and happiness of others, always shedding a Christian influence.”